Edinburgh Fringe Festival 2023

In 1964, ten years into the Vietnam war, the Canadian singer-songwriter Buffy Sainte-Marie wrote The Universal Soldier, as a reflection on individual responsibility for war and how the old feudal ways of thinking would eventually kill us. It became an iconic protest song, a global pacifist anthem.

Sixty years on, powerful men are still giving orders; further down the command chain those orders are being followed, lives lost, minds and bodies blown apart, social structures decimated.

Belfast man Norman Clements was a universal soldier, Royal Irish Fusilier 7043226. His World War II frontline service in Africa, Italy and Sicily left him deeply damaged, socially isolated, incapable of holding down a job and barely able to function as a husband and father.

Against the backdrop of the war in Ukraine and worldwide civil strife, actor and singer-songwriter Richard Clements has written a powerful, affectionate account of his grandfather’s troubled life in his UK Theatre Award-nominated solo play How to Bury a Dead Mule.

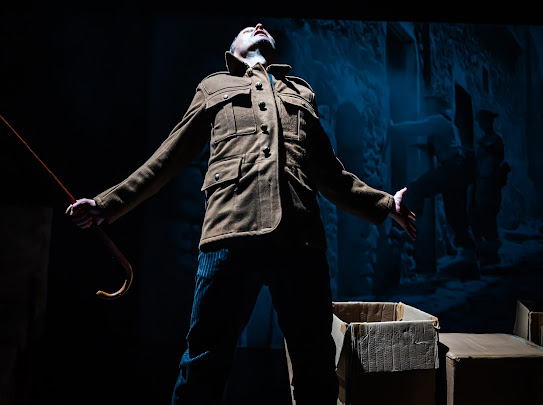

He acknowledges that Norman’s is one among many such experiences, but it’s the one that matters most to him. Under Matthew McElhinney’s inventive direction, and enhanced by Eoin Robinson’s videographic wizardry, his is no standard retelling of a sadly familiar story. Clements’s balletic performance, self-composed score, poetic prose and mixed media presentation transform an old soldier’s rambling recollections into a compelling piece of physical theatre.

“I’ve wanted to write this play for decades,” he says. “Years ago, I had a conversation with [fellow actor] Dan Gordon when we were doing Tim Loane’s play Caught Red Handed. He asked if I had an aspiration to write and I told him I’d love to write a play about my grandfather. Well, he said, just sit down and do it. But I could never find a way into it. A few years later, I was chatting to the screenwriter Anne Devlin on the set of Titanic Town. She suggested a good way to start was through a monologue – think of a character in your life who’s interesting and write it.

“I kept putting it off because my acting career was going pretty well. Every time I got a new job I’d be up and away and this would go onto the back burner. But, I’m also a songwriter and sometime poet. Eventually I got into it through the process of songwriting – write a few verses, write a chorus then develop the idea into something bigger”.

In 2020, the Covid lockdowns descended. Fired with renewed motivation, Clements sat down at the piano and wrote five instrumental pieces, whose titles were inspired by Norman’s journey. They now form the bedrock of the existing score.

“They became like a road map”, he says. “I was able take a piece of music, place it somewhere in my mind and start to build a kind of support structure around it. They were like little life rafts.

“The biggest inspiration in all this was my mum. She told me she had a huge pile of transcripts which she’d typed up from conversations with my granda. She’d compiled a mini-book called The Vision, because he claimed that in the mayhem of battle on Monte Cavallo, when he’d crawled off a minefield, he had a vision of the future, where he could see his family.

“A lot of PTSD sufferers talk about this, where the pain and torment of the battlefield is re-interpreted post-war as a religious awakening. I read those transcripts in all their detail and realised that this was him, this was Norman in his own words.

“I bookended them with reference to the Tonic cinema in Bangor, which had been converted into the care home where he spent his last years. I loved the idea of him resting his head every night in a place filled with cinematic memories. I thought it would be great if he could conjure up the ghosts of the past and bring in all those old soldiers to sit around and listen to his story”.

Clements was fascinated not only by Norman’s wartime experiences but by what subsequently happened to him when he came home. He describes his grandfather as “… a local character, a figure of fun, people went weird around him, they played cruel tricks on him, someone in a bar set fire to his trousers. Imagine!”

Clements’s mother Doreen, the second of Norman’s nine children, shared with him countless incidents of her father’s bizarre, chaotic behaviour and his uncontrollable anger towards politicians, employers and society in general, all of whom he felt had betrayed and rejected him.

“Mum remembers him going into a fish shop on the Holywood Road and buying a fish. He stood beside a post box, ranting and raving about being fired by the GPO. She says he delivered a speech to the people of Belfast and has a photograph of him holding the fish, with a woman looking at him in amazement. I wondered what he would have said in that speech, so I wrote it and I thought, that’s it, that’s PTSD Norman”.

Clements’s narrative carries tangential echoes of writers like Siegfried Sassoon, Stewart Parker and Frank McGuinness, in whose plays Northern Star, Pentecost and Observe the Sons of Ulster Marching Towards the Somme he has appeared. Shakespeare is present too in the depiction of his long-suffering grandmother Belle as a moving white light, whose single conversation with her husband is a verbatim segment from Lady Percy’s speech in Henry IV Part 1.

Unsurprisingly, some close family members have been unable to watch it. But his mother, who ran the A&E unit at the Ulster Hospital, has given it her wholehearted approval. Above all, Clements says, the play is an homage to Norman.

“It’s for him, 100%. I think he was a frustrated creative. After his death, we found loads of fragments of poetry and stories. What was he trying to do? Get something off his chest? Share something? The only thing he saw me in was Sons of Ulster. Afterwards he said, ‘I liked it. Keep doing what you’re doing, boy’.

“The way into this play was to find a poetic voice for him that he never had. I don’t know what he’d have made of it. He might have thought it odd, but I don’t think he would have questioned the reasoning for doing it. I can still hear his voice, ‘Keep doing what you’re doing’, and that feels nice”.

How to Bury a Dead Mule was performed at the Pleasance Dome, 2023 Edinburgh Fringe. It received only 4 and 5-star reviews and was nominated for the Mental Health Foundation Fringe Award.

This article first appeared in The Irish Times on 1 August 2023.